“A picture is worth a thousand words” is an English language adage referring to the notion that some complex ideas can be conveyed with just a single picture, conveying its meaning or essence more effectively than a description does (Wikipedia 2019). That certainly is the case in wound care, where a single wound photograph can capture severity, complexity, deterioration or improvement.

Purpose of Wound Photography

Health care providers take photos of wounds because it:

- Provides an accurate, objective and non-contact means of assessment;

- Is a cost-effective record of care;

- Assists with facilitating the diagnosis of a wound;

- Provides an objective record of healing and the impact of treatment on the wound;

- Reduces misinterpretation of wound assessment and progress between health care providers;

- Allows for a series of views that documents the wound over a period of time;

- Provides a documented record for medico legal reasons;

- Assists with teaching, research, publication (Hamilton and Fielder 2010, Santamaria et al. 2010)

- Instrumental in proving why certain treatments are needed through insurers (Kinsella 2002)

- May help the patient and family understand the serious nature of the wound, and prompt them to make informed choices (Wang et al. 2016).

Other Examples of Utilization

Initially used in research studies for assessment by a blinded assessor, wound photography has now become an everyday, front-line practice. Besides the purposes noted above, it can be used to improve aspects of care in other ways, such as:

1) Clinical Coaching and Mentoring

Clinical Coaching is a mentoring method that Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS) can use to assist nurses to strengthen areas of their practice and build skills that result in improved patient outcomes (Ervin 2005). Using digital wound photography, performing a wound assessment and transmitting this along with the current plan of treatment, the CNS can provide remote mentoring and coaching, embedding education and

evidence-based care in the response. Nurses report feeling supported in their role, with increased confidence in their wound care knowledge, receiving suggestions that they would not have thought of, and getting patients on the right pathway with effective treatment right away (CarePartners 2015, King 2014).

2) Virtual Wound/ Telemedicine

Figure 1 – Use of step by step (serial) photography

The benefits of using images for distant consultations (i.e. Telemedicine) in wound care have been described in the literature for the last two decades, reporting increased access to professional expertise in remote and rural settings, as well as cost savings. A 2014 multidisciplinary study in Long Term Care in Ontario demonstrated a cost savings of $650.00 per resident, with no difference in the rate of or time to healing (Stern et al. 2014). In 2016 the CICAT (wounds and healing town/hospital network) in Languedoc-Roussillon, France analyzed wounds treated using the remote consults and demonstrated 75% of wounds improved or healed, 72% reduction in the number of hospitalizations, and a 56% reduction in ambulance transfers to wound healing centers (Sood et al 2016). Real-world data such as this supports a wide-spread adoption of wound telemedicine. A systematic review and meta analysis of research in wound telemedicine in 2017 found that only 5 out of 118 articles met their inclusion criteria for the systematic review, and only 4 for the meta analysis. The authors cautioned that while the included papers had proven that telemedicine in wound care indeed improved the healing rate, it was inconclusive whether the wound size reduced in a given period (Goh and Zhu 2017). This paper is a stark comment on the lack of standardization and eligibility criteria in research studies. Experiential evidence such as provided by Sood et al (2016) gives a much clearer idea of the value of wound photography in everyday practice.

3) Pictorial instructions in complex care plans

Consider using step by step photographs when a plan of care such as pouching a fistula (Figure 1) or dressing a wound in a difficult anatomical location. Photographs will enhance the written instructions and are an asset to those who are visual learners. In her master’s thesis research, Beskrovnaya (2017) found that most nurses believed that a display of demographic and clinical data along with the wound care plan and corresponding wound images would be helpful in quickly grasping important information.

4) Validated and reliable method of providing wound assessment at a distance

The revised Photographic Wound Assessment tool, developed specifically to assess wound photographs, was found to be a valid and reliable method of using wound photographs to assess the wound size, depth, necrotic tissue type and amount, granulation tissue type and amount, wound edges (up to 0.5 cm) appearance and periwound viability (Thompson et al 2013). The study demonstrated that the tool had good inter- and intra- rater reliability and construct validity during the transition from film photography to digital photography, using both professional photographers and wound-care clinicians with access to basic cameras/ photographic equipment.

Tools meant to be used at the bedside to assess the wound include methods such as wound palpation or variables such as pain and odour, which cannot be obtained through photography alone. It is suggested that digital photography should be complementary to bedside assessment (Jeseda et al 2013).

5) Communication with physicians

Physicians understand the importance of wound photography. A survey to all members of the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons in 2013 found that 89% of responding surgeons and 100% of responding residents have taken photographs of patients using smartphones and believe they are both practical and necessary to provide the best patient care (Chan N et al. 2016). Community nurses would like to utilize wound photographs when communicating with physicians due to deterioration or changes in wound status, but patient privacy, security and confidentiality should be of concern whenever a photograph is taken. Secure networks and methods of transmission need to be in place.

6) Multidisciplinary team members who would not ordinarily see the wound can view the images

Many members of the multidisciplinary team are not normally present when wound dressing changes are being performed, even if wound care is within their scope of practice, such as physical therapists. Having a digital photographic record of the wound status makes it possible for them to understand the extent of the wound.

7) Increases productivity for wound care specialists

In a study to determine the productivity increase using digital imagery for better documentation and analysis, a significant time savings of 27 hours per day was realized for a specialised care centre with 10 nurses, using digital imagery wound measurements and analysis over manual wound documentation and measuring methods (Nair HKR 2018).

Regardless of the purpose, it is important that there be a comprehensive and consistent method of obtaining the images. Competency programs for wound photography can review important components such as patient confidentiality, camera technique, infection control, the accompanying nursing assessment (Buckley et al. 2005) and transmission and storage of electronic patient information

Consent and Patient Confidentiality

Any image that captures a patient’s condition constitutes part of his/ her medical record and, as such, should be held to the same standards of confidentiality and consent to disclosure as any written or dictated record (Taylor et al. 2008), as per legal privacy requirements. Whether for the purpose of documenting wounds, and/or for remote consultation purposes written informed consent should always be obtained from the patient, their substitute decision maker or parent/guardian. The consent should describe what the photograph is being used for (e.g. documentation, planning treatment, research, publication and/or educational purposes) and the patient should have the opportunity to decline any purpose they object to. It should also state that the images will be stored securely, and that members of the health care team will be able to access it. The photo forms part of the legal document that cannot be destroyed. When consent for wound photography is obtained from an incapacitated patient’s substitute decision maker, Institute of Medical Illustrators (2007) recommends that the photos be used strictly for clinical purposes.

Preventing cross-contamination

Because the screens of tablets and phones cannot be wiped down with disinfectant wipes, they must be protected from external contamination from soiled gloves, hands, and surfaces. Use hand sanitizer and apply clean new gloves before using for wound photography.

Identifying the Person in the Photograph

Use a paper ruler on which the client’s identification (as per agency policy- patient initials or billing reference number etc.) and the date is written with black indelible marker. If there is more than one wound to be photographed, identify the wound location on the ruler so that it can be seen in the photograph—e.g. Left medial malleolus, right heel etc. The ruler also provides a scale of comparison to estimate the wound size.

Lighting and background considerations

Use as much natural light as possible and keep artificial light use to a minimum – remember that too much natural light will overexpose too much artificial lamplight will give a golden glow and may distort the natural colours. Using a flash when there is enough natural light will cause a glare. On dark days or in rooms with poor natural light, turn on overhead or bedside lights. If you are facing a window or a bedside light, the wound will be in shadow, and the colour will be “washed out”.

Make the wound the only focus. Remove clutter from the background and use a white drape behind subject or limb (Sperring and Baker 2014). Avoid black or gray solid colours, or brightly patterned backgrounds. Photographers provide differing opinions on green and blue backgrounds: Hamilton and Fielder (2010) advise avoiding them, while Rodd-Nielsen and Ketchen (2014) recommend non-reflective greens and blues.

Positioning

Position the patient carefully so that the wound will be visible without fatigue to the client or photographer. Photographing a patient’s wound is usually easier while they are lying down or seated but having a client with a heel ulcer kneel on a chair to allow visualization and photography may be much easier than trying to lift the leg or position them on the side. Have a second person assist if needed to stabilize the area.

Preserving patient dignity

Drape the area so that genitalia, anal tissue or breasts are covered as much as possible to avoid embarrassment. Avoid capturing their face in the photo unless the wound is on or near the face; capture the area not the whole face if possible.

What is important to photograph?

Place the prepared paper ruler near the wound so that it will be included in the photograph. Remove the current dressing but place it beside the wound so that the colour and quantity of exudate is visible.

A close-up of the wound, showing the wound bed and periwound skin extending at least 2 cm is essential. If needed, take sequential photos pre- and post- cleaning / debridement of the wound. The latter may be important to demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of the debridement.

If undermining is present in the wound, draw a line with a medium tip indelible marker to demonstrate the extent of undermining in a photograph (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Use of marker to illustrate the extent of undermining

If cellulitis or dermatitis extends beyond the immediate peri-wound area, take an additional photo.

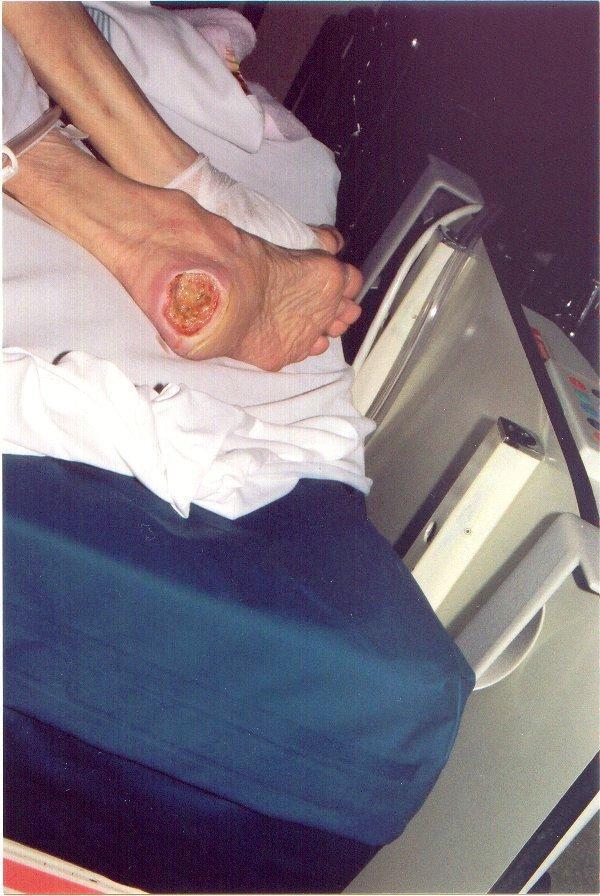

Figure 3 – More than simply the wound!

In a longer-view photo, include a point of anatomical reference to identify the location of the wound, such as the whole lower leg if it is a lower leg ulcer. Capture any other interesting features—for example if the patient is emaciated, has contractures, legs have pitting edema etc.

Take any additional photographs that contribute to the assessment of the treatment: for example, pressure redistribution surfaces, offloading devices for foot ulcers, less than optimally wrapped compression bandaging. Figure 3 is an example that captures several things of interest: the pressure redistribution surface, the location of the wound, the fact that there is an indwelling urinary catheter, and the very thin (low BMI) body of the patient. It ALSO shows that sheets are being used on TOP of the low-air loss surface, which interfere with the effectiveness.

Take the photo

Start by positioning the camera ½ metre from the wound and shoot at right angles or square (90 degrees – perpendicular) to the wound to avoid perspective distortion (Hamilton and Fielder 2010). Be sure to take a focused picture, and take more than one photo of each, so that you can pick the best ones afterwards.

Transmission and Storage

Patient photo documentation should be stored and kept as per the institution or agency’s medical records policies. If no policy exists for the storage of electronic files, it is recommended that these images be stored on a password-protected flash drive in a locked file drawer (Neilsen and Ketchen 2014). Retrieval and transmission of images should be done over a secure network; and any exchange over public or unsecured networks should be encrypted (ATA 2007).

Agencies and organizations must ensure that all efforts be taken to use appropriate information and communication technology (ICT) modalities with authentication, verification, confidentiality, and security arrangements and with full compliance with privacy laws (i.e. HIPAA, PIPEDA) laws. Software platforms should not be used when they incorporate social media (McKoy 2016).

If personal phones and tablets are used for patient photography, which is less than ideal, the photographs should be deleted as soon as they are transmitted or transferred to the patient record.

Conclusion

Easy, accessible wound photography has caused a paradigm shift in how we document and communicate wound care in our daily practice. Performed safely in a way that protects the patient’s health, dignity and privacy, it is a key component to wound care, and is essential in today’s world of health care.

Digital wound care platforms can provide a consistent, reproducible, easy to use photo documentation solution. Such approaches can overcome many of the challenges outlined in this document, both with regards to taking the photograph but also with respect to its transmission and storage.

References

- Hamilton A, Fielder K. Digital Photography in Wound Management. WoundsWest IT Solution – MMeX pilot 2010. University of Western Australia.

- Santamaria N, Glance DG, Prentice J,, Fielder K. The Development of an Electronic Wound Management System for Western Australia. Wound Practice & Research: Journal of the Australian Wound Management Association. 2010; 18(4):174-179.

- Kinsella A. Advanced telecare for wound care delivery. Home Health Nurse. 2002 Jul; 20(7):457-461.

- Wang SC, Anderson JA, Jones DV, Evans R. Patient perception of wound photography. IWJ. 2016; 13(3):326-330.

- Ervin NE. Clinical coaching: a strategy for enhancing evidence-based nursing practice. Clin Nurse Spec. 2005 Nov-Dec;19(6):296-301.

- CarePartners, Kitchener ON. Quality & Professional Practice Team update. August 2015.

- King B. Influencing dressing choice and supporting wound management using remote ‘tele-wound care’. British Journal of Community Nursing, 2014 19(Sup3), S24-31.

- Stern A, Mitsakakis N, Paulden M, Alibhai S, Wong J, Tomlinson G, Brooker AS, Krahn M, Zwarenstein M. Pressure ulcer multidisciplinary teams via telemedicine: a pragmatic cluster randomized stepped wedge trial in long term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Feb 24;14:83.

- Sood A, Granick MS, Trial C, Lano J, Palmier S, Ribal E, Téot L. The role of telemedicine in wound care: a review and analysis of a database of 5,795 patients from a mobile wound-healing center in Languedoc-Roussillon, France. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Sep;138(3 Suppl):248S-56S.

- Goh and Zhu. Effectiveness of Telemedicine for Distant Wound Care Advice towards Patient Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int Arch Nurs Health Care 2017; 3:070.

- Beskrovnaya A. Visual presentation of digital wound images: exploring community nurses’ preferences and attitudes. Master’s in Science in Nursing Thesis. University of British Columbia. 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/graduateresearch/42591/items/1.0362584

- Thompson N, Gordey L, Bowles H, Parslow N, Houghton P. Reliability and validity of the revised photographic wound assessment tool on digital images taken of various types of chronic wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2013 Aug;26(8):360-73

- Jesada EC, Warren JI, Goodman D, Iliuta RW, Thurkauf G, McLaughlin MK, Johnson JE, Strassner L. Staging and defining characteristics of pressure ulcers using photographs by staff nurses in acute care settings. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013 Mar-Apr;40(2):150-6.

- Chan N, Charette J, Dumestre DO, Fraulin FO. Should ‘smartphones’ be used for patient photography? Plast Surg (Oakv). 2016;24(1):32–34.

- Nair HKR. Increasing productivity with smartphone digital imagery wound measurements and analysis. J Wound Care. 2018;27(Sup9a): S12-S19.

- Buckley KM, Adelson LK, Hess CT. Get the picture! Developing a wound photography competency for home care nurses. Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2005 May-Jun; 32(3):171-177.

- Taylor DM, Foster E, Dunkin CS, Fitzgerald AM. A study of the personal use of digital photography within plastic surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg 2008;61:37-40.

- Institute of Medication Illustrators (IMI). IMI National Guidelines: clinical photography in wound management. United Kingdom. Institute of Medical Illustrators; 2007. Available from: www.imi.org.uk.

- Sperring B, Baker R. Ten Top Tips… Taking high-quality digital images of wounds. Wounds International. 2014; 5(1):7-8.

- Rodd-Nielsen E, Ketchen R. Remote Wound Consultation Series PART 1: Clinical Digital Photography: Tips and Techniques for Community Nurses. Wound Care Canada. 2014; 12(1):14-24.

- American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for teledermatology. 2007. Available from: www.researchgate.net/publication/308808284_Practice_Guidelines_for_Teledermatology

- McKoy K, Antoniotti NM, Armstrong A, Bashshur R, Bernard J, Bernstein D, Burdick A, Edison K, Goldyne M, Kovarik C, Krupinski EA, Kvedar J, Larkey J, Lee-Keltner I, Lipoff JB, Oh DH, Pak H, Seraly MP, Siegel D, Tejasvi T, Whited J. Practice Guidelines for Teledermatology. Telemed J E Health. 2016 Dec;22(12):981-990. Epub 2016 Sep 30.