A structured approach to wound assessment is required to maintain a good standard of care. This involves a thorough patient assessment, which should be carried out by skilled and competent practitioners, adhering to local and national guidelines (Harding et al, 2008). Inappropriate or inaccurate assessment can lead to delayed wound healing, pain, increased risk of wound complications, inappropriate use of treatments and a reduction in the quality of life for patients.

It is important that practitioners understand the elements of wound assessment: how to assess a wound; which wound assessment tools are available; and how to recognize a wound that may be failing to heal. The most important element is consistency, particularly in wound measurement as this is the key progress indicator.

What is a wound assessment?

A full and total assessment of the patient is essential to identify the causative or contributory factors that could potentially influence or delay wound healing. It is about assessing the wound, wound bed and comorbidities, planning appropriate interventions, evaluating their outcome and continual reassessment to demonstrate progress. Accurate, consistent and timely wound assessment underpins effective clinical decision making, enabling appropriate goals to be set for the management of the wound in order to manage morbidity and costs (Posnett et al, 2009).

There are many wound assessment tools available currently. However, evidence suggests that many patients are still not receiving comprehensive and knowledgeable wound assessment (Schultz et al,2004). This can lead to delayed wound healing, increased risk of infection, inappropriate use of wound treatments and a reduction in the quality of life for patients.

What Data is Needed to Complete Wound Assessment and Design a Care Plan?

Wound assessment should include a comprehensive assessment of the patient and also their wound to identify any factors that may influence healing. Results of all assessments must be clearly and accurately documented and include the recommended steps for reassessment.

Why should you Measure the Wound?

Wound measurement is an essential part of wound assessment. It should be recorded on initial presentation, and at regular defined intervals as part of the reassessment process. There are various methods available to measure wounds and it is important to use the same method each time, with the patient in the same position. Continuous monitoring of changes in wound size is an important way of evaluating response to treatment. One of the key data components relative to a patient’s wound care journey.

Why should you Document?

Good documentation promotes continuity of care through clear communication; demonstrates the quality of care delivered; and provides the evidence necessary for any legal proceedings (if it’s not written down; it didn’t happen).

Why Measure, Assess and Document?

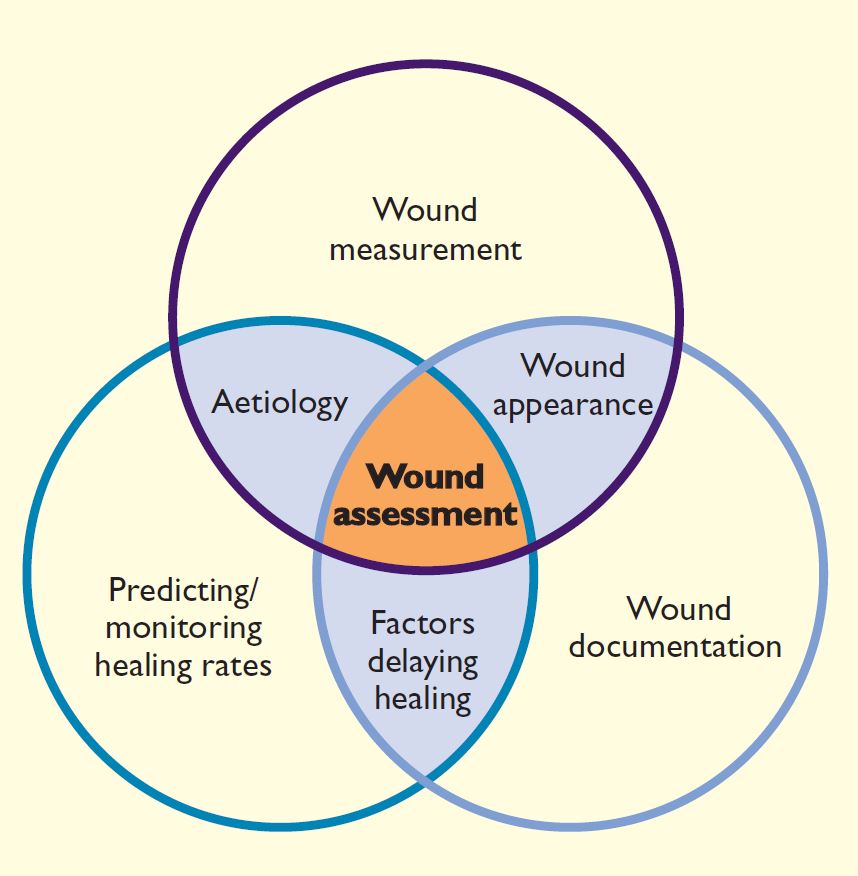

Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing and the first nursing epidemiologist, is attributed as saying “The ultimate goal is to manage quality. But you cannot manage it until you have a way to measure it, and you cannot measure it until you can monitor it” (Eagle and Davies 1993). Early in the Crimean War in 1854, she realized that more soldiers were dying of infections such as typhus, cholera and dysentery than from their war injuries. Hospital conditions were appalling, and finding herself without the authority to change practices, Nightingale collected data on the morbidity and mortality of the soldiers that she and her colleagues nursed. Back in England, she used the data to lobby for clinical and policy changes and succeeded in improving the standards of care. The importance of measuring and monitoring in order to manage is crucial in today’s wound care world, where, when poorly performed, they lead to inappropriate care and adverse outcomes. Initial and ongoing consistent, systematic documentation of wound characteristics are equally important, requiring continuous monitoring for complications and appropriate management (Krasner 1998, Sibbald et al 2000). These ARE best practices. Flanagan (2003) demonstrated the interdependent functions of wound assessment, wound size measurement and documentation in predicting and monitoring healing rates (Figure 1).

Methods of Measurement

The most commonly used wound measurements are length (L), width (W), and depth (D). Multiply L x W and you have the surface area (SA), multiply L x W x D and you have the volume of a wound, but only if the wound is the same depth in its entirety. Trace the wound with an indelible marker on an acetate sheet or transparent film, and you have the circumference. The wound measurement at the initial assessment is critical to calculate any change in wound size over time. Wound dimensions should become smaller as the wound heals with growth of granulation tissue and new blood vessels, reduction in tissue edema and migration of new epithelium from the edges (Keast et al 2004). Wounds will deteriorate if infection &/or necrosis occur. A wound may also appear to get larger as necrotic tissue is debrided, required to allow healing, but reflects the true size of the wound. Therefore, wound measurements alone are not enough to give a true picture; they must have qualitative descriptions as well .

Flanagan (2003) advises that to be of value, you must be able to compare measurement with the confidence that the previous person measuring the wound used the same technique or methodology, under the same conditions. The same wound measurement protocol should be used by all care providers, defining the specific procedure used to determine wound size and the frequency of measurements to minimise the margin of error in clinical practice.

Common difficulties in obtaining accurate wound measurements include determining exactly where and what ARE the wound edges, flexibility in wounds that are undermined or deep, natural curvatures of the body such as the calf of the leg or on the buttocks (Plassmann 1995), crevices or skin folds where the surrounding flesh must be manipulated to visualize the wound and to measure, and inconsistent positioning of the patient, which can change the contours and measurements. Circumferential leg ulcers or weeping legs with multiple denuded area are particularly daunting. Most authors agree that the method used by all clinicians who measure wounds must be the same, for comparative purposes over time. If overestimating surface area, but done using same technique, it will overestimate consistently and allow for comparability.

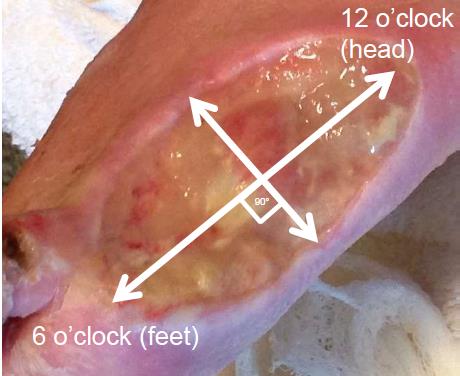

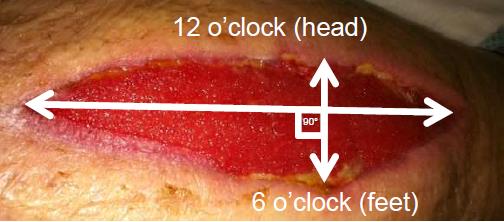

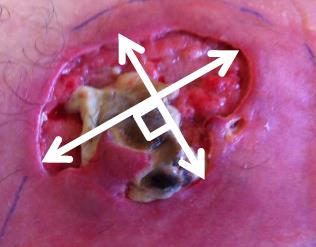

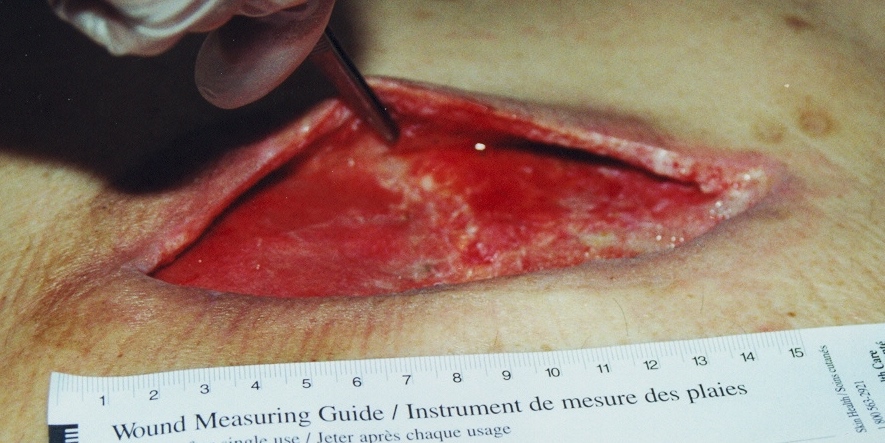

Wound Rulers

Usually formatted in centimetres, low-cost unsterile paper rulers are commonly used for point-of-care measurements, although instructions vary. You can measure the greatest length (head to toe) and the greatest width (side to side) perpendicular at a 90° right angle (Figure 2) to the first measurement, but this can be confusing if the wound is longer side to side, and shorter head to toe. An alternate, perhaps clearer method is to measure the wound end to end at the longest point for length and then perpendicular to this at the widest for width, regardless of the orientation (Figure 3). This reflects the Merriam-Webster definition of the word “length” as the longer or longest dimension of an object (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/length). This method is more valid and reliable than other ruler-based methods when used for circular or oval shaped wounds. but can overestimate the actual wound area by at least 44%, especially for wounds with irregular shapes (Figure 4) or those that curve around the body (Keast et al. 2004). L x W x D does not accurately reflect total volume when there is a variable depth, undermining or sinuses, but when done properly, wound volume is the most effective way to track the progress of deep wounds (Schubert and Zander 1996). Although they are single use, unsterile paper rulers pose a risk for wound contamination (Keast et al. 2004). Wounds should be cleaned well after measuring to reduce risk of contaminants.

Wound Tracings

This method is more accurate for irregular-shaped wounds. Accurately tracing the wound edges onto a transparency with an indelible marker can be a challenge, as the warmth of the body quickly vaporizes any wound exudate, causing the transparent material to mist up and make visualization of the wound edges a challenge. Secondly, what to do with the contaminated transparency? Ideally it will have two layers… one of transparent film that is in contact with the wound and is disposed of, and the top layer containing the tracing printed with a grid, usually in 1-centimetre sections, or the transparency can be set onto a grid paper. Either way you would count the number of squares to calculate the surface area. It is time-consuming and can be inaccurate when estimating partial squares (Keast et al. 2004). Studies have demonstrated that conventional contact tracing and square counting are not capable of determining the true area of a wound (Flanagan 2003 OWM).

How to Measure Depth

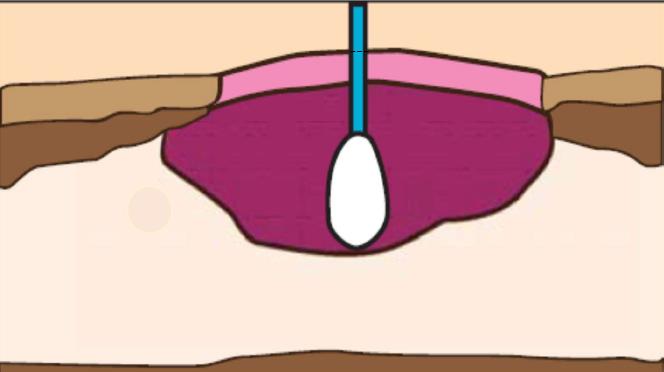

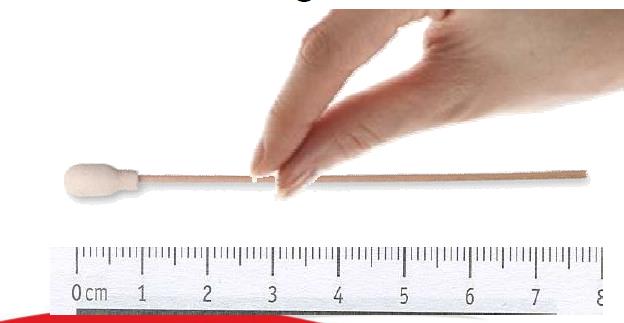

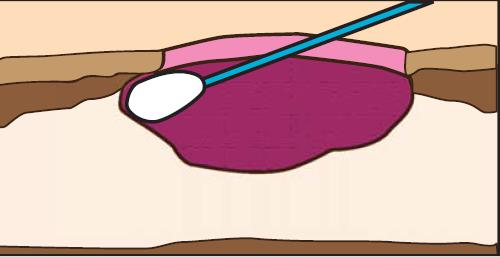

Gently measure deepest portion of the wound using a sterile cotton-tipped applicator or measurement device “straight in” (Figure 5) The depth is measured when the applicator shaft emerges at skin level. Pinch gloved fingers on the swab at skin level. Remove the applicator from the wound, keeping your fingers pinched in place on applicator, then determine the depth by placing it next to a measuring device (Figure 6). Estimate 0.1 cm for very shallow wounds (Harris et al 2010).

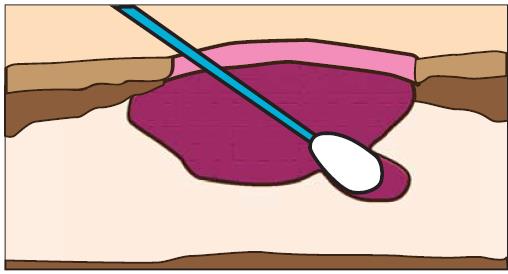

How to Measure Undermining and Sinus Tracts

The measurement of cavity wounds is difficult. The extent of tunnelling and the path of sinus tracts can be identified using a sterile cotton tipped applicator (Figure 7) but great care must be taken that the cotton tip does not come away and remain in the wound. Never use the end without the cotton applicator. The uncovered tip is sharp enough to perforate fascia and tissue if used with any force. If made from wood, there is a risk of splinters.

Evaluating the extent of undermining is critical to understanding the needs of the wound, as any undermined areas need to be resolved and the wound edges be firmly attached to the wound bed before healing can occur (Keast et al 2004) A sterile swab can be used to probe the entire wound margin, and the extent of undermining simultaneously (Figure 8 ) can be marked on the skin. The undermined area should be visualized if possible, using a sterile tongue depressor (Keast et al 2004) or blunt tipped forceps to gently lift the lip (Figure 9).

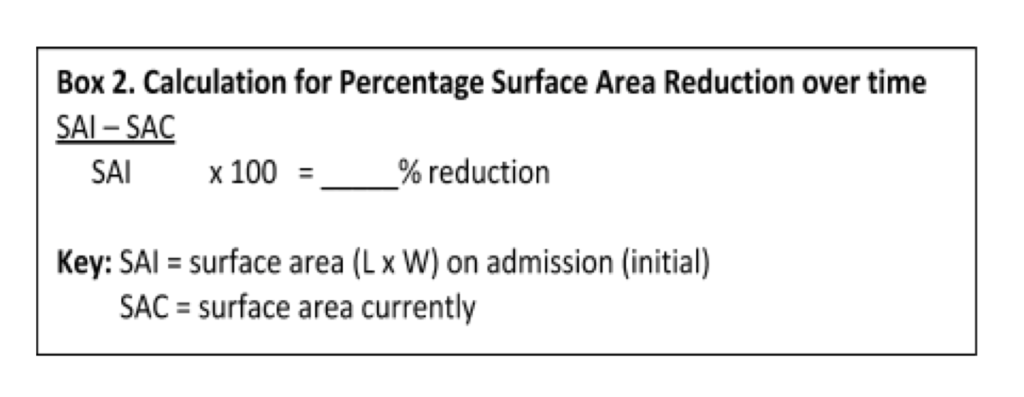

Calculating Percentage Change in Wound Size Over Time

A percentage surface area reduction (PAR) of 20-30% over the first 3 to 4 weeks of therapy is often used as an indicator that the wound is responding to the treatment and as a predictor of healing, in research (Margolis et al. 1999, Khoo and Jansen 2016) and by health care organizations. This can be determined using the calculation in Box 2 (Sussman and Bates-Jensen 2006) and recalculated at further points in time with simple wound measurements. PAR was validated as being as accurate by Cardinal et al. 2008, although they cautioned that it does not account for varying wound sizes and may not fully capture the magnitude of a particular wound’s healing response (e.g., the magnitude of a 50% reduction in wound size of 8 cm2 is not equal to the 50% reduction in wound size of 2 cm2).

Point-of-Care Wound Imaging and Planimetry

The digital age has seen the evolution of non contact digital solutions for wound measurements. With most, a target plate or scale gauge is placed in the same plane as the wound, and an image is captured with the use of a high-resolution camera and uploaded onto a computer. Digital image analysis is undertaken by specialized software, although some systems require manual tracing of the wound perimeter after the image is entered in the software app, which increases risk of error. The natural curvature of the body can cause distortion of wound surfaces (i.e. they are not flat). Large wounds may not be able to be captured completely in a single image, such as circumferential lower leg ulcers. A structured light or laser approach can combine more than one image, using a digital camera with projected laser beams that distort with the curvature, depth, and irregularity of a wound surface, creating a topographical model (Khoo and Jansen 2016).

Newer technology using a smartphone application, like Swift Skin and Wound, enables non-contact wound surface area and temperature measurements, described as an inexpensive, easy-to-use, reliable and accurate tool for wound measurement (Wang et al 2017). Sophisticated digital technology that is affordable will greatly increase the efficiency of assessing and documenting changes in wound healing, making it part of routine clinical practice (Flanagan OWM 2003, Khoo and Jansen 2016, Wang et al 2017).

Conclusion

The importance of accurate wound measurement and assessment is emphasized by clinical negligence cases involving wound mismanagement, many of which focus on failure to properly assess and monitor, document, report significant findings and communicate (Flanagan 2003 OWM, Scarborough 2016).

Wound measurement, assessment and documentation should be easy to use and perform, and not be a burden to care providers. Whatever the technique or technology it needs to be readily accessible, minimize inter-observer subjectivity, account for anatomical variations, and allow for quick, reliable and precise calculations of the wound area, used for sequential wound assessment and documentation.

See how Swift Skin & Wound Works:

References

- Andrews A, St Aubyn B. If it’s not written down; it didn’t happen. JCN. 2015; 29(5):20-22. Download

- Cardinal M, Eisenbud DE, Phillips T, Harding K. Early healing rates and wound area measurements are reliable predictors of later complete wound closure. Wound Repair Regen.2008 Jan-Feb;16(1):19-22.

- College of Nurses of Ontario Practice Standards. Documentation, Revised 2008. Updated April 2019. Download

- Eagle CJ, Davies JM. Current models of “quality”–an introduction for anaesthetists. Can J Anaesth. 1993 Sep;40(9):851-62.

- Flanagan M. Wound measurement: can it help us to monitor progression to healing? JWC. 2003; 12(5):189-194.

- Flanagan M. Improving Accuracy of Wound Measurement in Clinical Practice. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2003;49(10):28-40.

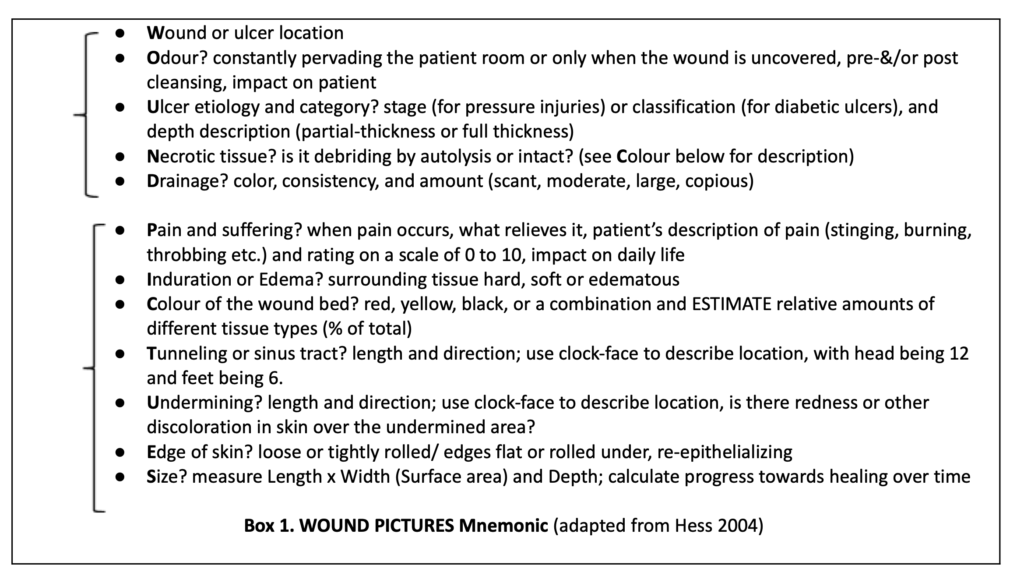

- Hess CT. Get the WOUND PICTURE. Adv Skin & Wound Care. 2004;17(7):330.

- Keast DH, Bowering CK, Evans AW, Mackean GL, Burrows C, D’Souza L. MEASURE: A proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Repair Regen. 2004 May-Jun;12(3 Suppl): S1-17.

- Khoo R, Jansen S. The Evolving Field of Wound Measurement Techniques: A Literature Review Wounds 2016;28(6):175-181.

- Krasner, D. (1998). Diabetic ulcers of the lower extremity: A review of comprehensive management. Ostomy/ Wound Management, 44(4), 56-75.

- Margolis, D.J., Berlin, J.A., & Strom, B.L. (1999). A comparison of sensitivity analyses of the effect of wound duration on wound healing. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 52, 123‐128.

- Orsted HL, Keast DH, Forest-Lalande L, Kuhnke JL, O’Sullivan-DrombolisD, Jin S, Haley J, Evans R. BEST PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE Prevention and Management of Wounds. Wounds Canada. 2018. Download

- Ousey K, Cook, L. Understanding the importance of holistic wound assessment. Practice Nursing. 2011; 22(6): 308–314.

- Plassmann P. Measuring wounds. JWC. 1995; 4(6): 269–72.

- Schubert V, Zander M. Analysis of the measurement of four wound variables in elderly patients with pressure ulcers. Adv Wound Care 1996; 9:29–36.

- Scarborough P. Legal and regulatory issues in wound care. American Medical Technologies Education Division. 2016. Download

- Sibbald RG, Williamson D, Orsted HL, Campbell K, Keast D, Krasner D, Sibbald D. Preparing the wound bed–debridement, bacterial balance, and moisture balance. Ostomy Wound Management. 2000 Nov;46(11):14-22, 24-8, 30-5; quiz 36-7.

- Sussman, C., Bates-Jensen, B. Part I: Introduction to wound diagnosis. Wound Care: A Collaborative Practice Manual. Third Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. 2006. Pg. 132.

- Virani T, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis DA, Berta W. Longwoods Review. Sustaining change: once evidence-based practices are transferred, what then? Healthcare Quarterly. 2009; 12(1):89-96.

- Wang SC, Anderson JAE, Evans R, Woo K, Beland B, Sasseville D, Moreau L. Point-of-care wound visioning technology: Reproducibility and accuracy of a wound measurement app. PLOS ONE. 2017; 12(8): e0183139. Download